"On my honor, I will do my best. To do my duty...." Millions of male Americans could probably finish the statement I began. It is the Scout Oath, recited by Boy Scouts for the past century, and by yours-truly from the age of thirteen until I reached legal adulthood and so "aged out" of Scouting into manhood. Manhood, masculinity, and crises of masculinity are all fodder for future posts. Similarly, the American Scouting movement - modeled after the paramilitary organization for youths founded by Lord (and General) Robert Baden-Powell in Britain to prepare scrawny and unmotivated urban boys for combat with anticipated Continental foes, can be dealt with in future. Let me focus here on honor.

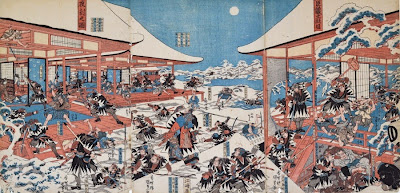

Half a lifetime ago, I discovered that I am related by name - if not by blood - with the clan that gifted Japan with her national legend - all the more powerful for being rooted in fact - of samurai honor, or bushido. The story of the "Chushingura" - more familiarly known in the English-speaking world as "The Tale of the 47 Ronin" or "The Treasury of Loyal Retainers - established in the national consciousness the sense that a true warrior died upon his sword rather than give up (or wait two years to exact vengeance, and then fall upon one's sword... *spoiler alert*). Without spoiling the story, the public disgrace of their lord led to his suicide and the attainting of the Asano Clan's lands, and dozens of now-masterless samurai (or ronin). Many of the ronin vowed to take revenge rather than merely look for a new master (and steady employment). They duly sought this bloody method of regaining their honor in 1703, knowing that even if they succeeded in slaying the aristocrat who destroyed their lord, their own lives would be forfeit. Ironically - historians will appreciate this - this event took place in 1703, a century after one Japanese warlord used Western military technology to defeat his rivals, declared himself shogun, expelled Western influences, and turned his conquered warlords and their samurai armies into glorified courtiers reminiscent of Louis XIV's Versailles. The samurai remained armed-to-the-teeth, however, and if no longer able to engage in large wars under the shogun's hegemony, they turned to street duels. More tragically, the loyalty-beyond-death of 47 masterless samurai of the Asano Clan infused Japanese soldiers in the 1930s and '40s with a contempt for surrender - their own or their enemy's - leading to horrific (and racialized) combat against soldiers and civilians in China and the Pacific Theater of World War II. In twentieth-century Japan, films lauding the loyal samurai were made every few years. Tomorrow, the United States experiences the first Hollywood-inflected version (complete with mythical Japanese creatures like oni and kappa and a woman-who-turns-into-a-dragon... oh yes, and Keanu Reeves).

Lest anyone think that I write this (already potentially narcissistic blog post) in a narcissistic attempt to advertise my aristocratic blood, the good news is that my illustrious 33-year-old ancestor-in-question's hot temper forced him to commit suicide (friends who are familiar with my temper - in my intemperate youth, that is - will appreciate this). It is rather his loyal samurai-turned-ronin who are the heroes of the hour. Indeed, if one visits their cemetery at Sengaku-ji in Tokyo, one finds the 47 samurai sharing the same "level" with their lord.

Honor is a "funny" thing. As a historian of race and slavery, I learned early on in graduate school that to be a slave was to be "without honor." Every year, every day, every moment that a slave breathed without rising up against the master to grasp liberty-or-death was proof of the slave's worthiness for slavery and not liberty, and complete lack of honor. See historian Francois Furstenberg's work on this subject for American concepts of honor in the context of slavery and citizenship. Yet slaves could - and did - rise up to grasp freedom. Spartacus remains a shining ("white") example from Roman history. Every American living today knows something about what happened on 9/11/2001. But most have not heard about the events of September 11, 1851 in Christiana, Pennsylvania. Near dawn on that day, over one hundred African Americans and white Quakers defied the Fugitive Slave Law when a Baltimore County planter named Edward Gorsuch (there is a Gorsuch Avenue in Baltimore today) and a federal marshall sought to recapture two of Gorsuch's self-emancipated slaves, leading to a confrontation and gunfire. Gorsuch died in the exchange of bullets, and his son was mortally wounded. As he rode a train towards Canada to escape Fugitive Slave Law "justice" (the infamous Dred Scott Supreme Court decision still six years away), one of the self-emancipated resistants was told by a fellow passenger: "All you colored people should look at [the shootout at Christiana] as we people look at our brave men, and do as we do. You see [the fugitive slaves were] not fighting for a country, nor for praise. [They were] fighting for freedom: [they] only wanted liberty, as other men do." They certainly did, and they defended it with their lives, fortune, and sacred honor. But in 1851 - six years before the highest court in the land declared that African Americans had no rights that white men were bound to respect - acts of honor must be followed by discretion and escape to Canada, unless one wanted to embrace the fate of the 47 ronin.

For those who have watched and enjoyed the film "300" about Leonidas' 300 Spartans who fought and died to a man to defend the pass of Thermopylae against "barbarian" Persian invaders, one might not know that one of the rites of passage to become a full-fledged Spartan citizen-warrior was to murder a slave. The Spartan gained honor and standing in a society based upon slavery by ending the life of one utterly lacking in honor. In the early twenty-first century, honor for a significant number of religious conservatives around the globe is tied up in the sexual purity of adolescent girls. The shame of rape can be expunged by killing the victim, an "honor killing." Honor - or honour - has a fraught history. The public acclaim - and full rights of citizenship - that falls upon the hero is tingling to those who have demonstrated martial prowess, yet at what price? What is honor when it is dependent upon the dishonor (or shaming) of others? Could Achilles have been content with slaying the Trojan hero Hector without stooping to dishonor his body by dragging it behind his chariot in full view of Troy in the Illiad? Can it be a positive quality without negative attendants? What if anything is honorable to preserve about honor? Or in the twenty-first century (at least for the cynical academic) is the only useful remnant of honor culture the negative sense of being able to shame "heroes" who act dishonorably?

Parting Shot

I will take a brief hiatus to enjoy the holidays. But with New Years and the AHA Annual Meeting approaching, expect more academic job market material, soon.

Your obedient servant,

The History Major

Honor is indeed a funny thing - of course there is the saying that it is always better (and more difficult) to live with honor than to die with honor - but really what it comes down to is that honor that demands satisfaction via evil acts is no honor at all.

ReplyDelete